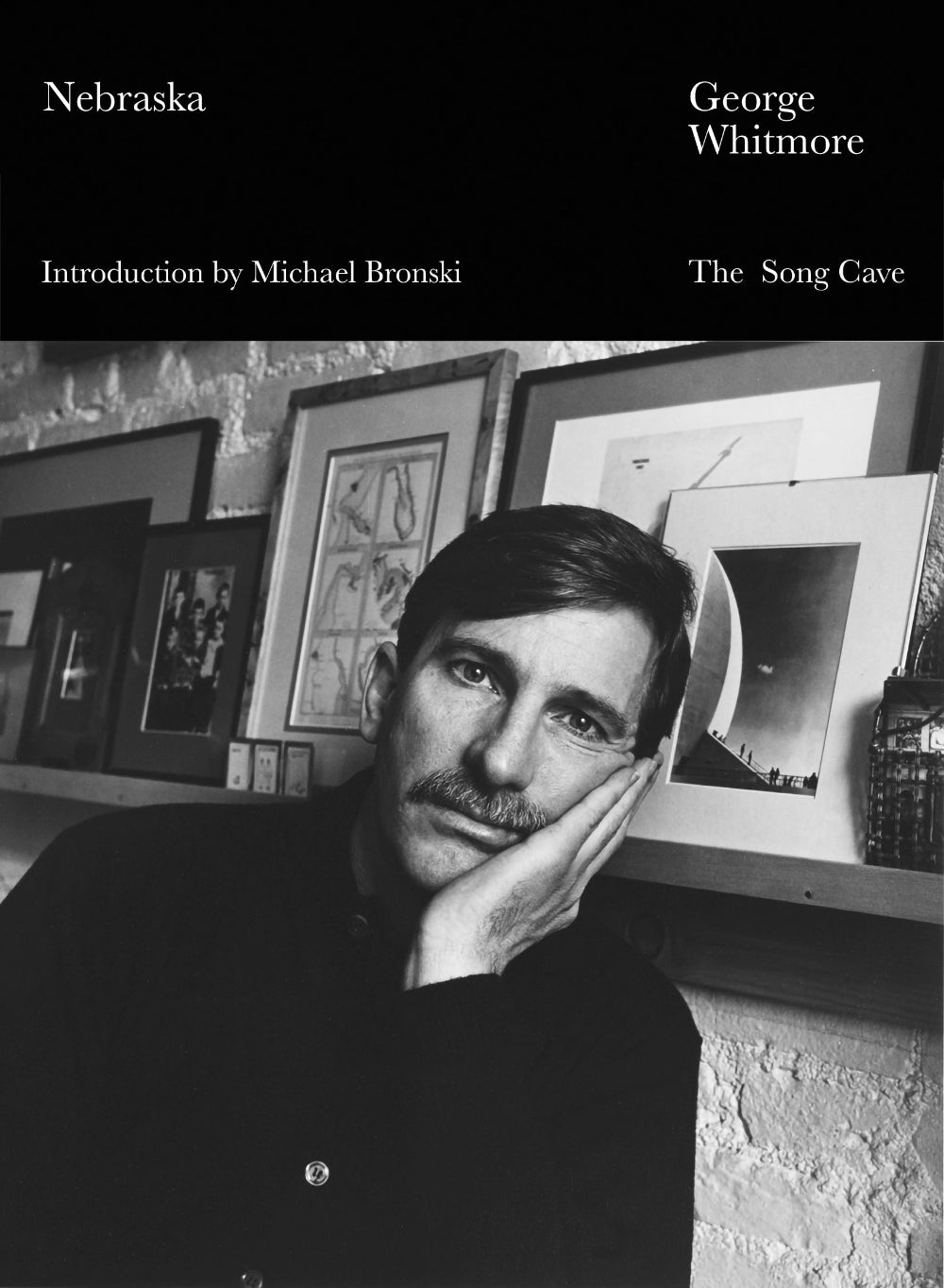

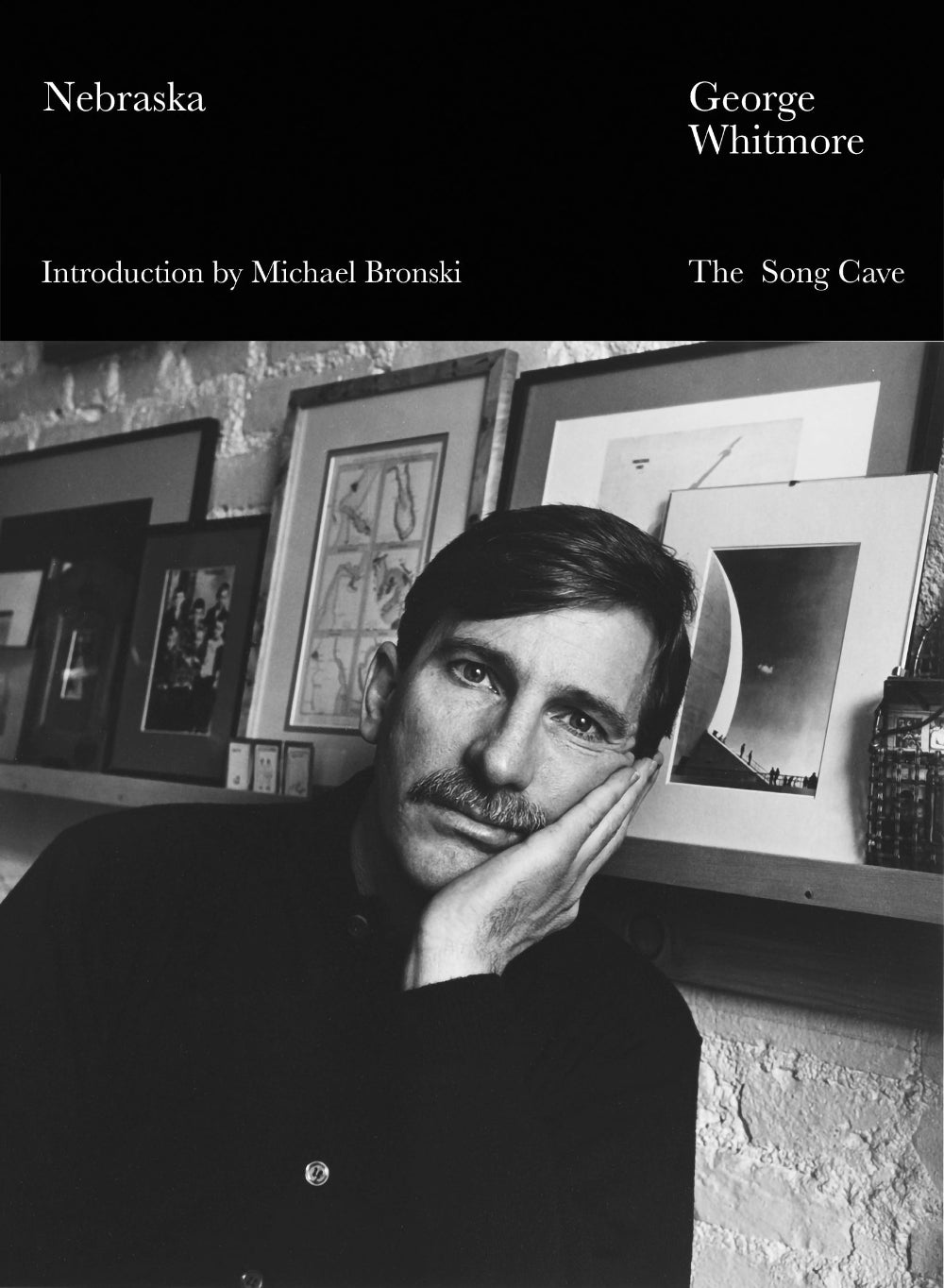

Nebraska by George Whitmore

Nebraska by George Whitmore

Couldn't load pickup availability

Introduction by Michael Bronski.

First published in 1987 by Grove Press and long out of print, Nebraska is a classic underground novel by the gay writer and activist George Whitmore. Craig McMullen, a young boy in Nebraska, gets hit by a car on the way to get groceries on his bike. After having his leg amputated, he is bed-ridden, lonely, bored, and addicted to painkillers. His rare interactions with kids his own age, specifically with a neighbor boy who often spends the night, awaken within Craig feelings to further explore. When Craig’s uncle moves into the family home after serving time in the Navy, a world of hope, pain, mystery, and despair descends upon Craig and the McMullen family, giving the reader glimpses into how gay lives were secretly lived and horrifically extinguished in 1950s rural America. After a life of trauma and yearning, the adult Craig’s search for redemption and clarity ultimately lead him on a circular path. With an unforeseen ending that can only be described with the delicately complicated touch of Whitmore’s enigmatic prose, Nebraska will stay in your mind long after finishing it.

This book is beyond good. It is perfect. It may be the Great American Novel.

–John Whittier Treat

Vacillating between Denis Johnson's deadpan realism and Joe Brainard's acerbic longing, Nebraska is a rare achievement in American letters, wherein Queer rurality is not a site of deprivation or estrangement--but power, capacity, and collective reckoning. Nearly lost to history, the novel--and its author-- is now mercifully salvaged, a book ahead of its time brought back to life.

–Ocean Vuong

George Whitmore's rawboned disturbing masterpiece chronicles working-class queer Midwestern life in the 1950s through the coming-of-age of a boy and his uncle. Nebraska belongs in the canon of novels that look tenderly on the horrors of familial homophobia and state repression. Whitmore’s prose calls to mind Willa Cather & William S. Burroughs & even Jack Kerouac. Too much of our literature has been lost to the ongoing pandemics of AIDS and homophobia. We are very lucky to have this gorgeous edition of this lost classic, to be so haunted.

–Andrea Lawlor

Of all the writers in the Violet Quill, George Whitmore had perhaps the snarkiest and most critical vision of gay life, from his first book, The Confessions of Danny Slocum, about a man unable to achieve an orgasm, to what many consider his masterpiece, Nebraska. And his earlier career in the theater gave him a keen sense of the dramatic, all on view in this wonderful last book.

–Andrew Holleran

No southern comfort here, no prairie romance… Whitmore has carved the most economical of nutshells, and I am astounded by his verve, his swerve, as we say, away from the antecedent masters of proletarian grotesque. Read Nebraska in an afternoon and remember it, as I am doing, with an enduring shudder, a continuing realization that these little thistles have a wrong beauty of their own.

–Richard Howard

Nebraska is nothing less than stunning… George Whitmore belongs in the company of Louise Erdrich, Alice Walker, Augustin Gomez-Arcos, and a few others who cross the line from gifted to brilliant… I would like to see everyone in the world read this book… Whitmore’s Nebraska is perfect.

–Edge

George Whitmore (September 27, 1945 – April 19, 1989) was an American playwright, novelist, and poet. He also wrote non-fiction accounts about homosexuality and AIDS. Raised in Denver, he received a BA degree in English and Theatre from MacMurray College in Jacksonville, Illinois, in 1967. Whitmore was awarded a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and pursued graduate studies in the Theatre Department at Bennington College.

Once in New York City, Whitmore worked for Planned Parenthood (1968-1972) and the Citizens Housing and Planning Council of New York (1972-1981). Whitmore wrote poetry and short stories that were published in both gay and straight periodicals, as well as issued under his own imprint, the Free Milk Fund Press, which was headquartered in his Upper West Side apartment. Three of Whitmore's plays were produced in New York: The Caseworker (1976), Two Plays for Three Women: Flight/The Legacy (1979), and The Rights (1980), and three of his novels were also published: The Confessions of Danny Slocum (1980), Deep Dish (serialized between 1980 and 1982), and Nebraska (1987). The latter, loosely based on Whitmore's childhood memories, was developed from an earlier unproduced play and written during his residencies at the Edward Albee Foundation (1983) and the MacDowell Colony (1985). Whitmore was a member of a literary group known as the Violet Quill, whose seven authors are regarded as the strongest voices of the gay male experience in the post-Stonewall era: Christopher Cox, Robert Ferro, Michael Grumley, Andrew Holleran, Felice Picano, and Edmund White.

At the same time, his personal and professional communities were rapidly being overtaken by the AIDS epidemic, as gay male friends and colleagues around him began to get sick and die. Whitmore's response was perhaps his most important contribution to non-fiction literature: three interrelated articles and one book that focused on the human face of AIDS. Relying on his reporting skills and journalism contacts, he fashioned the first article for a general public already frightened by rising morbidity statistics: “Reaching Out to Someone With AIDS,” a profile of the daily life of an AIDS patient and his volunteer advocate, appeared in The New York Times Magazine.

A second article, “Someone Was Here,” ran in GQ the next year. Whitmore reused the title for his 1988 book, Someone Was Here: Profiles in the AIDS Epidemic, which expanded on his Times article by looking at the lives of patients’ families and medical professionals as well as the patients themselves, thereby emphasizing the toll of the disease on both the heterosexual and homosexual populations. In the essay, “Bearing Witness,” Whitmore revealed that he too was a victim of AIDS, having been diagnosed a year after the publication of his “Reaching Out” article. He was 43 years old when he died in New York on April 19, 1989, from AIDS-related complications, two years after the publication of Nebraska.